In the Central African Republic, one in four children has been displaced.[1] Conflict and violence, food and economic insecurity, and poor to non-existent access to clean water and health care are the norm for millions of families.[2] The country is also one of the world’s least prepared to manage a COVID-19 outbreak: Nationwide, only 100 COVID-19 tests are available and there is only one COVID-19 treatment centre with 14 beds in the capital city, Bangui.[3] Unable to protect themselves from the virus and its impacts, both physical and socioeconomic, displaced families stand to see their already fragile lives further threatened. And for their children, this means even greater insecurity.

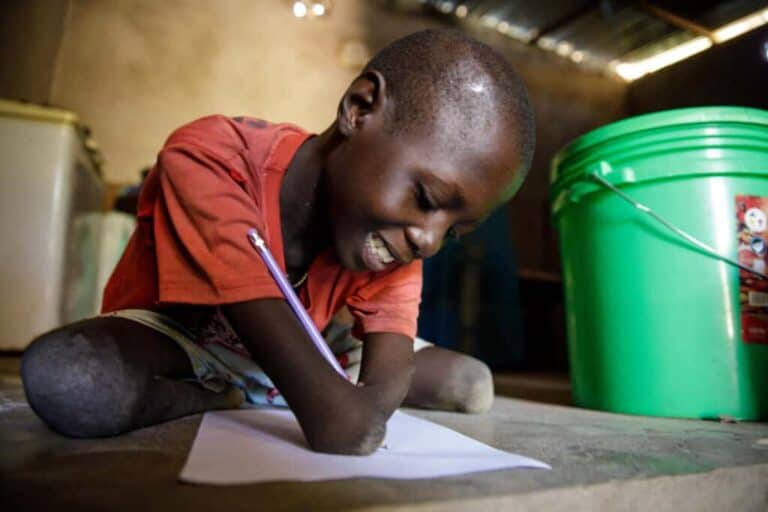

From the Central African Republic to Afghanistan, Venezuela to Greece, children around the world find themselves living in precarious circumstances because they have been displaced from home. Migrant, refugee and internally displaced children face intense deprivations in their right to well-being — economic uncertainty, limited access to school, poor health care, and threats to their safety and protection. Their vulnerability is likely to intensify as COVID-19 spreads among migrant and displaced communities, as explored in a new article, “Migrant and Displaced Children in the Age of COVID-19”, recently published in Migration Policy Practice.

The quickly changing legal landscape has left millions of migrant and displaced children in limbo.

Regulations on travel have left migrants, asylum-seekers and refugees stranded or turned away, placing children and their families at risk of further harm and potentially separating them. Restricted travel is also disrupting the humanitarian supply chain and the vital assistance provided by relief workers.

Migrant and displaced children often live in families that are susceptible to economic shocks.

COVID-19 has pushed the global economy into the deepest recession since the Great Depression. Vulnerable populations – such as the poor, migrants and displaced persons – are likely to experience these economic impacts with disproportionate force. Migrant workers are particularly at risk as restrictions are enacted on access to places of work in destination countries and on return to families.[4] As economic pressures mount, more children may drop out of school, seek work, migrate, or be subjected to child marriage or trafficking.

Extreme overcrowding, limited access to latrines and water, and poor health care leave displaced families exposed and unprotected.

Basic measures like social distancing and hand-washing often cannot be followed for those who have migrated or been displaced, and in many cases, doctors won’t be available when a family member falls sick. Half of migrant children and over 90 per cent of displaced children live in low- and middle-income countries where health systems were already overwhelmed and under capacity before the spread of COVID-19. These families may also be excluded from vital public health information. And, as options for health care and psychosocial support further contract, underlying conditions among displaced children – such as malnutrition and communicable and non-communicable diseases – and psychological ailments can worsen.[5]

For learners living in displacement, their education will now be more limited or disappear completely.

Many migrant and displaced children have already missed substantial time in the classroom. Access to online resources and reliable electricity will be out of reach for many, especially those living in remote locations, refugee camps or informal settings. In sub-Saharan Africa, where more than a quarter of the world’s refugees reside, 89 per cent of learners do not have household computers and 82 per cent lack Internet access.[6] As access to school is curtailed, more children may drop out; some will be called to work. Return to the classroom after the pandemic subsides will become even more difficult.

The safety and security of migrant and displaced children will further erode as incomes are lost and family members succumb to the virus.

Daily life is already challenging in many humanitarian settings – now, the pandemic-related stresses of lockdowns, income loss, and confinement to small places are further undermining children’s safety.[7] If parents or caregivers fall sick or die, children from migrant and displaced families will be left to fend for themselves. Economic downturns typically lead to more children working, getting pregnant or married, and being trafficked or sexually exploited.[8] These impacts are likely to be even more acutely felt among children on the move. Stigma, xenophobia and discrimination towards migrant and displaced populations are also reaching new levels of concern in countries around the world.

Many of the pandemic’s broad-ranging, long-term humanitarian and socioeconomic impacts on migrant and displaced children have yet to be seen. We must ensure the health, safety, and protection of these ultra-vulnerable children today, and for the future. This means sound policies and urgent actions are needed to put migrant and displaced children at the forefront of preparedness, prevention and response to COVID-19.

More information on displacement and COVID-19

References

[1] In 2018, around 330,000 refugee children from the Central African Republic in 2018 found asylum outside of the country (United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, 2019; unpublished data) and 303,000 were displaced within the country’s own borders in 2019 due to conflict and violence (Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre, Number of IDPs by Age at the End of 2019, April 2020).

[2] United Nations Children’s Fund, ‘Crisis in the Central African Republic: In a neglected emergency, children need aid, protection – and a future’, UNICEF Child Alert, November 2018, see link.

[3] United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, Global Humanitarian Response Plan

COVID-19, April–December 2020, version as of 28 March 2020.

[4] International Organization for Migration, ‘COVID-19 Places Migrant Workers in Highly Vulnerable Situations’, 26 March 2020, see link.

[5] International Rescue Committee, COVID-19 In Humanitarian Crisis: A double emergency, April 2020, see link; Save the Children, COVID-19: Operational guidance for migrant & displaced children, April 2020, see link.

[6] United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization, ‘Startling Digital Divides in Distance Learning Emerge’, Press release, 21 April 2020, see link.

[7] United Nations Children’s Fund, ‘COVID-19: Children at heightened risk of abuse, neglect, exploitation and violence amidst intensifying containment measures’, Press release, 20 March 2020, see link.

[8] Human Rights Watch, ‘COVID-19’s Devastating Impact on Children’, 9 April 2020, see link.