“Poverty is when you don’t have any money. Because of a lack of money, children don’t have a chance to develop. They may not have a good profession or a good foundation for life.” This is how Marieta and Gor from Armenia recently described the impact of poverty. Whether it’s the instant loss of income that so many parents face as a result of COVID-19 or the austerity measures that may follow plummeting GDP, children will bear the brunt of this pandemic long after the virus itself has been eradicated.

Projections change daily, with some predictions that the recession that follows COVID-19 will be the worst global crisis since World War II. As a result, up to 106 million more children could live in poor households by the end of the year, according to new projections from UNICEF and Save the Children. This is on top of the 385 million children living in extreme poverty before COVID-19 hit, and the 663 million children living in multidimensional poverty, meaning monetary poverty combined with poor health, lack of education, inadequate living standards, or exposure to environmental hazards, disempowerment or the threat of violence.

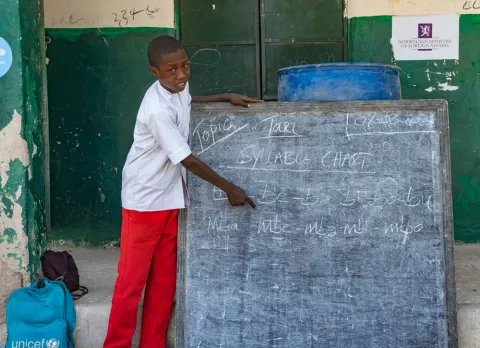

When these stark economic predictions manifest, we will witness the first time in 30 years that global poverty has increased. What deepens the tragedy is that children are disproportionately affected by poverty. Not only are they twice as likely to live in poverty than adults, they are also more forcefully affected by its consequences. Children living in poverty are less likely to go to school, more likely to be forced into child labor, more likely to be married as children, and less likely to access nutritious food and quality healthcare. “We are worried that our children won’t have enough to eat,” said Siriphon Yampikul, of Thailand. “We parents can go without food, that is OK. But our children cannot go without.”

The threat to children is not limited to the near term. The recovery phase will take years, especially in low- and middle-income countries where there is limited capacity to mitigate the impact of the economic slowdown. In Sub Saharan Africa for instance, temporary measures were introduced and existing programmes were scaled up following the 2008 crisis – but were constrained by weak social protection systems, low pre-existing coverage, and decreased revenues. And you don’t need to look too far back in history to know that when a crisis hits, budget cuts often follow an initial spike in government spending on the response. These austerity measures produce devastating results for children. If the response to COVID-19 follows the same pattern, we will see how unequally and cruelly economic destruction is distributed. Families on the cusp of escaping intergenerational cycles of poverty will be flung back in. In East Asia and the Pacific, for example, the virus is expected to keep almost 24 million people in poverty who would otherwise have escaped. And for children living in countries already affected by conflict, fragility, and violence, the impact of this crisis will add to an already precarious situation, increasing further risks of instability.

Families on the cusp of escaping intergenerational cycles of poverty will be flung back in

Although past crises offer a grim picture of what’s to come, they also provide valuable insight into how we might mitigate the impact. UNICEF supports governments and partners in more than 100 countries to design and implement social protection systems and measures such as cash transfers, which can play a major role in cushioning the impact of financial crises on households with children. Currently, 2 out of 3 children have no access to any child or family benefits. Rapidly expanding these programmes to reach every child is a critical investment not just in children and families, but also in a world better prepared for future shocks. As one child in Trinidad said: “Poverty upsets my community. It affects you and me.” In addition to expansion of coverage, social protection responses must consider children’s specific needs and vulnerabilities, including those related to gender and disability.

We are already seeing good signs. Many countries are expanding social protection programmes. In Thailand, for example, the cabinet has approved in principle a top-up of 1,000 baht (around 32 US$) for 3 months for the Child Support Grant, Disability Grant, and Old Age Allowance, following advocacy by UNICEF in collaboration with other UN agencies.

The World Bank is deploying $160 billion to help governments protect the poor and vulnerable, support businesses, and bolster economic recovery. And there are mounting calls for debt relief to support low- and middle-income countries.

In countries everywhere, however, the scale of the solution has to match the scale of the problem. Governments must take decisive action to prevent child poverty from deepening and inequality from worsening within and across countries. They must rapidly extend cash transfer programmes to reach every child, invest in family-friendly policies, such as paid leave and accessible, affordable childcare, and expand access to healthcare and other services. In the medium and longer term, they will need to strengthen and expand shock responsive social protection systems to make children, communities and economies more resilient.

The economic impacts of COVID-19 are without precedent in modern history. Unprecedented action to protect children and their families from the worst effects should be a fundamental yardstick for success.

David Stewart is Chief of Child Poverty and Social Protection at UNICEF HQ.

Sola Engilbertsdottir is a Policy Specialist at UNICEF HQ.